KOÆ Atlas (Abandoned)

King Of the Ancients and Empires

Atlas

Please refer to me as Atlas

Mongolian Empire

The Mongol Empire (Mongolian: Mongolyn Ezent Güren Mongolian Cyrillic: ???????? ????? ?????; Mongolian pronunciation: [m??g(?)?'i?? ?t?s'?nt 'gur??]; also ????, 'the Horde' in Russian chronicles) existed during the 13th and 14th centuries and was the largest contiguous land empire in history. Originating in the steppes of Central Asia, the Mongol Empire eventually stretched from Eastern Europe and parts of Central Europe to the Sea of Japan, extending northwards into Siberia, eastwards and southwards into the Indian subcontinent, Indochina and the Iranian Plateau; and westwards as far as the Levant and the Carpathian Mountains.

The Mongol Empire emerged from the unification of several nomadic tribes in the Mongol homeland under the leadership of Genghis Khan, whom a council proclaimed ruler of all the Mongols in 1206. The empire grew rapidly under his rule and that of his descendants, who sent invasions in every direction. The vast transcontinental empire connected the East with the West with an enforced Pax Mongolica, allowing the dissemination and exchange of trade, technologies, commodities and ideologies across Eurasia.

The empire began to split due to wars over succession, as the grandchildren of Genghis Khan disputed whether the royal line should follow from his son and initial heir Ögedei or from one of his other sons, such as Tolui, Chagatai, or Jochi. The Toluids prevailed after a bloody purge of Ögedeid and Chagataid factions, but disputes continued among the descendants of Tolui. A key reason for the split was the dispute over whether the Mongol Empire would become a sedentary, cosmopolitan empire, or would stay true to their nomadic and steppe lifestyle. After Möngke Khan died (1259), rival kurultai councils simultaneously elected different successors, the brothers Ariq Böke and Kublai Khan, who fought each other in the Toluid Civil War (1260–1264) and also dealt with challenges from the descendants of other sons of Genghis. Kublai successfully took power, but civil war ensued as he sought unsuccessfully to regain control of the Chagatayid and Ögedeid families.

During the reigns of Genghis and Ögedei, the Mongols suffered the occasional defeat when a less skilled general was given a command. The Siberian Tumads defeated the Mongol forces under Borokhula around 1215–1217; Jalal al-Din defeated Shigi-Qutugu at the Battle of Parwan; and the Jin generals Heda and Pu'a defeated Dolqolqu in 1230. In each case, the Mongols returned shortly after with a much larger army led by one of their best generals, and were invariably victorious. The Battle of Ain Jalut in Galilee in 1260 marked the first time that the Mongols would not return to immediately avenge a defeat, due to a combination of the death of Möngke Khan, the Toluid Civil War between Arik Boke and Khubilai, and Berke of the Golden Horde attacking Hulegu in Persia. Although the Mongols launched many more invasions of the Levant, briefly occupying it and raiding as far as Gaza after a decisive victory at the Battle of Wadi al-Khazandar in 1299, they withdrew due to various geopolitical factors.

By the time of Kublai's death in 1294, the Mongol Empire had fractured into four separate khanates or empires, each pursuing its own separate interests and objectives:

Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also referred to as the Eastern Roman Empire and Byzantium, was the continuation of the Roman Empire in its eastern provinces during Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, when its capital city was Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul, which had been founded as Byzantium). It survived the fragmentation and fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD and continued to exist for an additional thousand years until it fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.[2] During most of its existence, the empire was the most powerful economic, cultural, and military force in Europe. Both "Byzantine Empire" and "Eastern Roman Empire" are historiographical terms created after the end of the realm; its citizens continued to refer to their empire simply as the Roman Empire (Greek: ?as??e?a ??µa???, tr. Basileia Rhomaion; Latin: Imperium Romanum), or Romania (??µa??a), and to themselves as "Romans"

Several signal events from the 4th to 6th centuries mark the period of transition during which the Roman Empire's Greek East and Latin West divided. Constantine I (r. 324–337) reorganised the empire, made Constantinople the new capital, and legalised Christianity. Under Theodosius I (r. 379–395), Christianity became the Empire's official state religion and other religious practices were proscribed. Finally, under the reign of Heraclius (r. 610–641), the Empire's military and administration were restructured and adopted Greek for official use instead of Latin. Thus, although the Roman state continued and its traditions were maintained, modern historians distinguish Byzantium from ancient Rome insofar as it was centred on Constantinople, oriented towards Greek rather than Latin culture, and characterised by Orthodox Christianity.

The borders of the empire evolved significantly over its existence, as it went through several cycles of decline and recovery. During the reign of Justinian I (r. 527–565), the Empire reached its greatest extent after reconquering much of the historically Roman western Mediterranean coast, including North Africa, Italy, and Rome itself, which it held for two more centuries. During the reign of Maurice (r. 582–602), the Empire's eastern frontier was expanded and the north stabilised. However, his assassination caused the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628, which exhausted the empire's resources and contributed to major territorial losses during the Early Muslim conquests of the seventh century. In a matter of years the empire lost its richest provinces, Egypt and Syria, to the Arabs. During the Macedonian dynasty (10th–11th centuries), the empire again expanded and experienced the two-century long Macedonian Renaissance, which came to an end with the loss of much of Asia Minor to the Seljuk Turks after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071. This battle opened the way for the Turks to settle in Anatolia.

The empire recovered again during the Komnenian restoration, such that by the 12th century Constantinople was the largest and wealthiest European city. However, it was delivered a mortal blow during the Fourth Crusade, when Constantinople was sacked in 1204 and the territories that the empire formerly governed were divided into competing Byzantine Greek and Latin realms. Despite the eventual recovery of Constantinople in 1261, the Byzantine Empire remained only one of several small rival states in the area for the final two centuries of its existence. Its remaining territories were progressively annexed by the Ottomans over the 14th and 15th century. The Fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 finally ended the Byzantine Empire. The last of the imperial Byzantine successor states, the Empire of Trebizond, would be conquered by the Ottomans eight years later in the 1461 Siege of Trebizond

.

Carthage Empire

According to Polybius, Carthage relied heavily, though not exclusively, on foreign mercenaries,[94] especially in overseas warfare. The core of its army was from its own territory in Northwest Africa (ethnic Libyans and Numidians (modern northern Algeria), as well as "Liby-Phoenicians"—i.e., Phoenicians proper). These troops were supported by mercenaries from different ethnic groups and geographic locations across the Mediterranean, who fought in their own national units; Celts and Balearics and Iberians were especially common. Later, after the Barcids conquered Iberia[dubious – discuss] (modern Spain and Portugal), Iberians came to form an even greater part of the Carthaginian forces.

Carthage seems to have fielded a formidable cavalry force, especially in its Northwest African homeland; a significant part of it was composed of light Numidian cavalry. Other mounted troops included North African elephants (now extinct), trained for war, which, among other uses, were commonly used for frontal assaults or as anticavalry protection. An army could field up to several hundred of these animals, but on most reported occasions fewer than a hundred were deployed. The riders of these elephants were armed with a spike and hammer to kill the elephants, in case they charged toward their own army. The Carthaginians also fielded troops such as slingers, soldiers armed with straps of cloth used to toss small stones at high speeds.

The navy of Carthage was one of the largest in the Mediterranean, using serial production to maintain high numbers at moderate cost. The sailors and marines of the Carthaginian navy were predominantly recruited from the Phoenician citizenry, unlike the multiethnic allied and mercenary troops of the Carthaginian armies. The navy offered a stable profession and financial security for its sailors. This helped to contribute to the city's political stability, since the unemployed, debt-ridden poor in other cities were frequently inclined to support revolutionary leaders in the hope of improving their own lot.] The reputation of her skilled sailors implies that training of oarsmen and coxswains occurred in peacetime, giving their navy a cutting edge in naval matters.

The trade of Carthaginian merchantmen was by land across the Sahara and especially by sea throughout the Mediterranean and far into the Atlantic to the tin-rich Cassiteridesand also to Northwest Africa. Evidence exists that at least one Punic expedition, that of Hanno, may have sailed along the West African coast to regions south of the Tropic of Cancer.

Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire, or the Triple Alliance (Classical Nahuatl: Excan Tlahtoloyan, ['jé??ka?n? t??a?to?'ló?ja?n?]), began as an alliance of three Nahua altepetl city-states: Mexico-Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan. These three city-states ruled the area in and around the Valley of Mexico from 1428 until the combined forces of the Spanish conquistadores and their native allies under Hernán Cortés defeated them in 1521.

The Triple Alliance was formed from the victorious factions in a civil war fought between the city of Azcapotzalco and its former tributary provinces. Despite the initial conception of the empire as an alliance of three self-governed city-states, Tenochtitlan quickly became dominant militarily. By the time the Spanish arrived in 1519, the lands of the Alliance were effectively ruled from Tenochtitlan, while the other partners in the alliance had taken subsidiary roles.

The alliance waged wars of conquest and expanded rapidly after its formation. At its height, the alliance controlled most of central Mexico as well as some more distant territories within Mesoamerica, such as the Xoconochco province, an Aztec exclave near the present-day Guatemalan border. Aztec rule has been described by scholars as "hegemonic" or "indirect". The Aztecs left rulers of conquered cities in power so long as they agreed to pay semi-annual tribute to the Alliance, as well as supply military forces when needed for the Aztec war efforts. In return, the imperial authority offered protection and political stability, and facilitated an integrated economic network of diverse lands and peoples who had significant local autonomy.

The state religion of the empire was polytheistic, worshiping a diverse pantheon that included dozens of deities. Many had officially recognized cults large enough so that the deity was represented in the central temple precinct of the capital Tenochtitlan. The imperial cult, specifically, was that of Huitzilopochtli, the distinctive warlike patron god of the Mexica. Peoples in conquered provinces were allowed to retain and freely continue their own religious traditions, so long as they added the imperial god Huitzilopochtli to their local pantheons.

Frankish Empire

largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Franks during Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. It is the predecessor of the modern states of France and Germany. After the Treaty of Verdun in 843, West Francia became the predecessor of France, and East Francia became that of Germany. Francia was among the last surviving Germanic kingdoms from the Migration Period era before its partition in 843.

The core Frankish territories inside the former Western Roman Empire were close to the Rhine and Maas rivers in the north. After a period where small kingdoms inter-acted with the remaining Gallo-Roman institutions to their south, a single kingdom uniting them was founded by Clovis I who was crowned King of the Franks in 496. His dynasty, the Merovingian dynasty, was eventually replaced by the Carolingian dynasty. Under the nearly continuous campaigns of Pepin of Herstal, Charles Martel, Pepin the Short, Charlemagne, and Louis the Pious—father, son, grandson, great-grandson and great-great-grandson—the greatest expansion of the Frankish empire was secured by the early 9th century, by this point dubbed as the Carolingian Empire.

During the Carolingian and Merovingian dynasties the Frankish realm was one large kingdom polity subdivided into several smaller kingdoms, often effectively independent. The geography and number of subkingdoms varied over time, but a basic split between eastern and western domains persisted. The eastern kingdom was initially called Austrasia, centred on the Rhine and Meuse, and expanding eastwards into central Europe. It evolved into a German kingdom, the Holy Roman Empire. The western kingdom Neustria was founded in Northern Roman Gaul, and as the original kingdom of the Merovingians it came over time to be referred to as Francia, now France, although in other contexts western Europe generally could still be described as "Frankish". In Germany there are prominent other places named after the Franks such as the region of Franconia, the city of Frankfurt, and Frankenstein Castle.

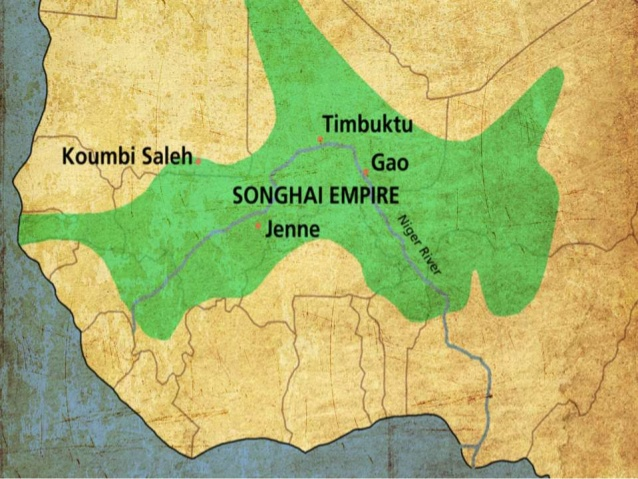

Songhai Empire

as a state that dominated the western Sahel in the 15th and 16th century. At its peak, it was one of the largest states in African history. The state is known by its historiographical name, derived from its leading ethnic group and ruling elite, the Songhai. Sonni Ali established Gao as the capital of the empire, although a Songhai state had existed in and around Gao since the 11th century. Other important cities in the empire were Timbuktu and Djenné, conquered in 1468 and 1475 respectively, where urban-centered trade flourished. Initially, the empire was ruled by the Sonni dynasty (c.?1464–1493), but it was later replaced by the Askia dynasty (1493–1591).

During the second half of the 13th century, Gao and the surrounding region had grown into an important trading center and attracted the interest of the expanding Mali Empire. Mali conquered Gao towards the end of the 13th century. Gao would remain under Malian hegemony until the late 14th century. As the Mali Empire started to disintegrate, the Songhai reasserted control of Gao. Songhai rulers subsequently took advantage of the weakened Mali Empire to expand Songhai rule.

Under the rule of Sonni Ali, the Songhai surpassed the Malian Empire in area, wealth, and power, absorbing vast areas of the Mali Empire and reached its greatest extent. His son and successor, Sonni Baru (1492–1493), was a less successful ruler of the empire, and as such was overthrown by Muhammad Ture (1493–1528; called Askia), one of his father's generals, who instituted political and economic reforms throughout the empire.

A series of plots and coups by Askia's successors forced the empire into a period of decline and instability. Askia's relatives attempted to govern the empire, but political chaos and several civil wars within the empire ensured the empire's continued decline, particularly during the brutal rule of Askia Ishaq I (1539–1549). The empire experienced a period of stability and a string of military successes during the reign of Askia Daoud (1549–1582/1583). Ahmad al-Mansur, the Moroccan sultan at the time, demanded tax revenues from the empire's salt mines.

Askia Daoud responded by sending a large quantity of gold as gift in an attempt to appease the sultan. Askia Ishaq II (1588–1591) ascended to power in a long dynastic struggle following the death of Askia Daoud. He would be the last ruler of the empire. In 1590, al-Mansur took advantage of the recent civil strife in the empire and sent an army under the command of Judar Pasha to conquer the Songhai and to gain control of the Trans-Saharan trade routes. After the disastrous defeat at the Battle of Tondibi (1591), the Songhai Empire collapsed. The Dendi Kingdom succeeded the empire as the continuation of Songhai culture and society.